What does it mean to bear witness to events? What responsibility does the act of witnessing carry? These are the central questions evoked by George Azar and Mariam Shahin’s documentary film “Beirut Photographer.” Released on Al Jazeera English in part to remember the thirtieth anniversary of the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon–and more particularly of Beirut–the film is a multi-layered and fascinating portrayal of the often contradictory aspects of battles that would become subsumed under the label of the “Lebanese civil war,” as well as of the process, and cost, of documenting conflict.

The film initially centers on photographer and filmmaker George Azar. He introduces himself as having Lebanese heritage and explains his interest and fascination with the Middle East: “Like a lot of Arab-American kids, […] the Middle East was a mystery to me” until, he states, the Palestinian liberation struggles of the 1970s put the region at the forefront of people’s consciousness in new ways. Upon graduating from UC Berkeley, he picked up a camera and, with hardly any experience whatsoever, landed in Beirut in 1981 to visually document the war. His timing was, in a sense, optimal for such a move – it included the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon and the accompanying brutal eighty-day siege of Beirut, followed by the PLO’s exile to Tunis, the massacres at Sabra and Shatila in September of that year, the definitive battles at Baddawi camp in northern Lebanon in 1983, and the general havoc wrought on the country’s human and political infrastructures.

[Beirut. Photo by George Azar.]

An idealistic young man when he landed in Lebanon, Azar grew up quickly. He was kidnapped multiple times, captured by the Israelis, held at gunpoint, and put up against a wall to be executed. He witnessed combat, death, the loss of youth and innocence, hypocrisy and the effects of political corruption, in hundreds of photographs. Thirty years after he first arrived in the land of his ancestors, he returned with a selection of those photographs in an attempt to locate their subjects and hear the stories of their lives, as he puts it, "outside the frame.”

In a recent interview with Jadaliyya, Azar gave a précis of some of the moments of reconnection in the film. The flower shop owners who lose a son; the Palestinian family, displaced yet again, seeking refuge; the “Smurfs,” as the teenaged gunmen he befriended referred to themselves. “Beirut Photographer” visually brings these and other characters to life as Azar returns to visit people whose lives he captured in his lens for an instant. He clearly loves his work and holds a deep affinity and affection for Beirut and for Lebanon – you hear it in his voice as he narrates the film and in the sensitivity with which he speaks of the people in his photographs. He is gentle and respectful when he encounters them again decades later, understanding that the war may still be a painful subject to reflect upon.

Yet “Beirut Photographer” occasionally slips into melodrama and the kind of stereotyping one does not expect to see in a film made by a photojournalist – i.e. someone who witnesses in a manner that allows him to comprehend the multi-dimensionality and contradictions of conflict. What is more, in what appear to be attempts at inserting elements of drama, the film relinquishes nuance and even accuracy. Slips in Azar’s narration include statements like “I’ll never forget seeing Lebanon from the air, burning.” Overly dramatic statements like this can be chalked up to both poetic license (here he is describing the intense experience of being forcibly flown out of Lebanon by the Israeli army) and to the selective memory of an individual in a traumatic situation. But they are disappointing and problematic when used in the context of a documentary film that is not only about the personal perspective of Azar but also about historical events. In this sense, the interface between Azar’s memory and an overarching historical narrative gets a bit wrinkled.

[Beirut. Photo by George Azar.]

Another problematic statement comes when he discusses Israel’s renewed occupation of South Lebanon. Azar states that the “Israelis underestimated the Lebanese in the South,” and that a coalition of Amal and Hizballah “began a resistance campaign” that ultimately “drove the Israelis out” in 2000. The narrative sequence, even allowing for time limitations imposed by a film, is a sort of historical hopscotch whereby it sidelines the much more complicated aspects of this coalition and skips over the tensions that belie a simplified teleological formula of resistance + coalition = liberation.

Puzzling too, are the moments when the film simultaneously romanticizes and demonizes its subject matter. In his discussion of teenaged fighters, for example, Azar describes the low-income, Shi‘a neighborhood of Shiyyah as “the most dangerous neighborhood in the most dangerous city in the world.” Even allowing for Shiyyah’s location as a stone’s throw from ‘ground zero’ of hostilities in 1975 and its consistent treacherousness throughout the conflict, how could it possibly compare with other equally if not more dangerous neighborhoods or cities around the world at the time? What is the point of making such a sensationalist declaration here? Moreover, what does “dangerous” even mean in this context? Unfortunately, “Beirut Photographer” tosses such statements into the mix with little scaffolding to hold them in place other than Azar’s understandably horrifying experiences on the front lines. It further reminds us that bearing witness to events in no way implies a more authentic view of the bigger picture (literally). The finality of a photographed moment, frozen as it is, is not the last word. These solecisms in the film’s narration do a disservice to Azar and Shahin’s otherwise sensitive and carefully crafted film.

[Beirut civilians. Photo by George Azar.]

Viewers may also be left asking questions about Azar’s choices: why follow up with these photographs in particular? What, exactly, did finding these people mean? He partially answers the last question when he implies wanting to find some consolation–one may venture to say closure--for what he has called the most formative period of his life. But one wishes for a little more introspection in the film about Azar’s sense of accountability and responsibility to the people he lived with, sought shelter with, and befriended during the conflicts. What did he think returning might mean to the people in the pictures? Photojournalists rarely go in search of the people they photographed. What does the unusualness of this journey suggest about the larger costs of this profession and the burden of responsibility that bearing witness entails?

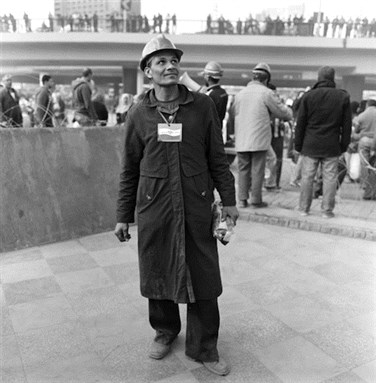

[Zutti, West Beirut, 1984. Photo by George Azar.]

In its seamless shifting between 1982 and 2012, the film poses important questions about memory and its “uses” – so to speak – both in general and during times of war and trauma. It pushes us to ask what responsibility we have when engaging with other people’s memories. What does it mean to pull people back into those moments? How do we hand memories back to people, as Azar does literally when he gives the subjects photographs depicting what is likely one of the most vulnerable moments of their lives? Who ‘owns’ that memory, the photographer who captures it yet who remains outside the frame, or the picture’s subjects? In the end, after all, they were both there and both suffered, although in different ways and in different degrees.

By revisiting his photographs, and in visiting their human subjects, Azar reminds us of the details that people can still call up, decades later – gold bangles, a corridor, a pair of socks. In that vein, one of the things “Beirut Photographer” does best is illustrate the strength, power, and longevity of memory. It may seem an obvious point – yet is one that colonizers, invaders, corporations, and dictators continue to ignore at their peril.

“Beirut Photographer” began airing on 5 December as part of Al-Jazeera English’s Witness series.

![[A boy in Martyrs Square, Beirut at the end of the wars, sells photos of the square as it appeared before the wars. Photo by George Azar.]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/Azar_MartyrsSquare.jpg)